The eye is the lamp of the body: when your eye is clear, your whole body also is full of light…

“What do you see?” Grandma Agbaje pointed at the small window to her right and returned her gaze to those of us in her teenage Sunday school class. Our gazes moved to the window, and some of us stood on our toes.

“The window!”

“A window with silver aluminium sill,”

“A tree just outside it,”

“A blue and white sky,” I said after others had made their tries.

“Is that all there is to see?” Grandma Agbaje asked instead of giving the reply we all anticipated. I prided myself on always getting an answer right and waited confidently. Instead, she launched into a Yoruba song.

To ba n rin l’okunkun

Ko le mo, afoju ni

To ba n jeun eleera

Ko le mo, afoju ni

To ba r’omoge to rewa eeeh

Ko le mo rara

If he’s walking in the dark

He cannot know, he is blind

If he is eating ant-infested food

He cannot know, he is blind

If he sees a beautiful girl, yes

He can never know

Tope Alabi—Afoju

“Is that all there is to see?” She asked for the last time, and I thought she only wanted to mess with our heads. Anybody with eyes could see what she pointed at.

That Sunday School, Grandma Agbaje had instilled something in us. My father was a tough man who had acquired a crisscross of wrinkles from frowning his entire life.

“Dad is tough and unapproachable,” My siblings and I discussed among ourselves. We attributed this to his frowns and gruff voice. The feelings of unfulfillment he bore as a burden were not visible to us.

Now a lead pastor, I watched Grandma Agbaje’s sons walk into the church with their families in navy blue Aso ebi for Grandma’s burial. The first son walked in with an expectedly gloomy face. He removed his fila, revealing a shock of greying hair amidst other jet-black strands. I noticed the red beads indicating his chieftaincy status on his wrists. It made some sense that he thought that I was too young to officiate at his mother’s funeral. Our last conversation had made that too clear.

The second son, Ireoluwa was all smiles and even made funny faces at his six-year-old daughter. But I had seen him mop tears off his face in his car at the parking lot. So much for the independent middle-born and extrovert among the three children.

I was hardly surprised when Ololade, the only daughter rushed into the church in a super tight skirt with twin babies. While her husband followed on her heels, carrying a heavy-looking bag in his hands. Her other children just walked in like typical unconcerned teenagers. Experience with my wife told me that it was a possibility that she had asked her tailor to sew an emergency cloth using an old measurement. And I was comfortable with the possibility that my speculations were wrong.

I cleared my throat before mounting the pulpit for the brief sermon for Grandma Agbajes’ final church ceremony. I smiled at Ireoluwa, who returned the smile with tears in his eyes. His emotions were contagious, and I sniffed as I thought about my father. He had not lived up to Grandma Agbaje and had died being misunderstood by his children.

“Grandma Agbaje’s body is dead, and she’s now with the Lord,” I said, putting aside the first sentence that came to mind. It was about the Lord giving and taking lives.

I found Chief Agbaje’s deep-set eyes fixed on me after the sermon. He already knew about the Lord’s ability to give and take. The Lord took his mother away after he had just returned to faith. He was her final assignment.

“Pastor,” I heard someone call after the service. I was comforting the others who spoke in hushed tones. Grandma Agbaje was old enough to die and had led a fruitful life, but they had hoped she would live up to another decade.

I turned around to the voice. It was the Chief. “Thank you, Pastor,” He said with a nod and turned, his Agbada trailing him.

I smiled. I saw someone who was trying to adjust to the new development. The Chief was also trying to respect the pastor he had deemed unqualified for his mother’s last rites.

Sighing as I sat on my chair at my office, I whipped out my phone. I was to place a call to my wife. She wanted to know how I had fared sending off one of my mentors and ministry intercessor to her eternal home. But the screen on my phone only mirrored the strains on my face.

“What do you see?” Grandma Agbaje’s voice cut through again.

“Man of God is trying his best not to fall apart in tears,” I said, doing some self-evaluation.

But that Sunday, Grandma Agbaje had asked us to do an exercise. And one by one, we stood where she had stood, pointing to the window.

“Close an eye,” She said. The exercise only left us more confused than ever. Then, she removed her signature brown glasses from her face. One of her eyes was blind.

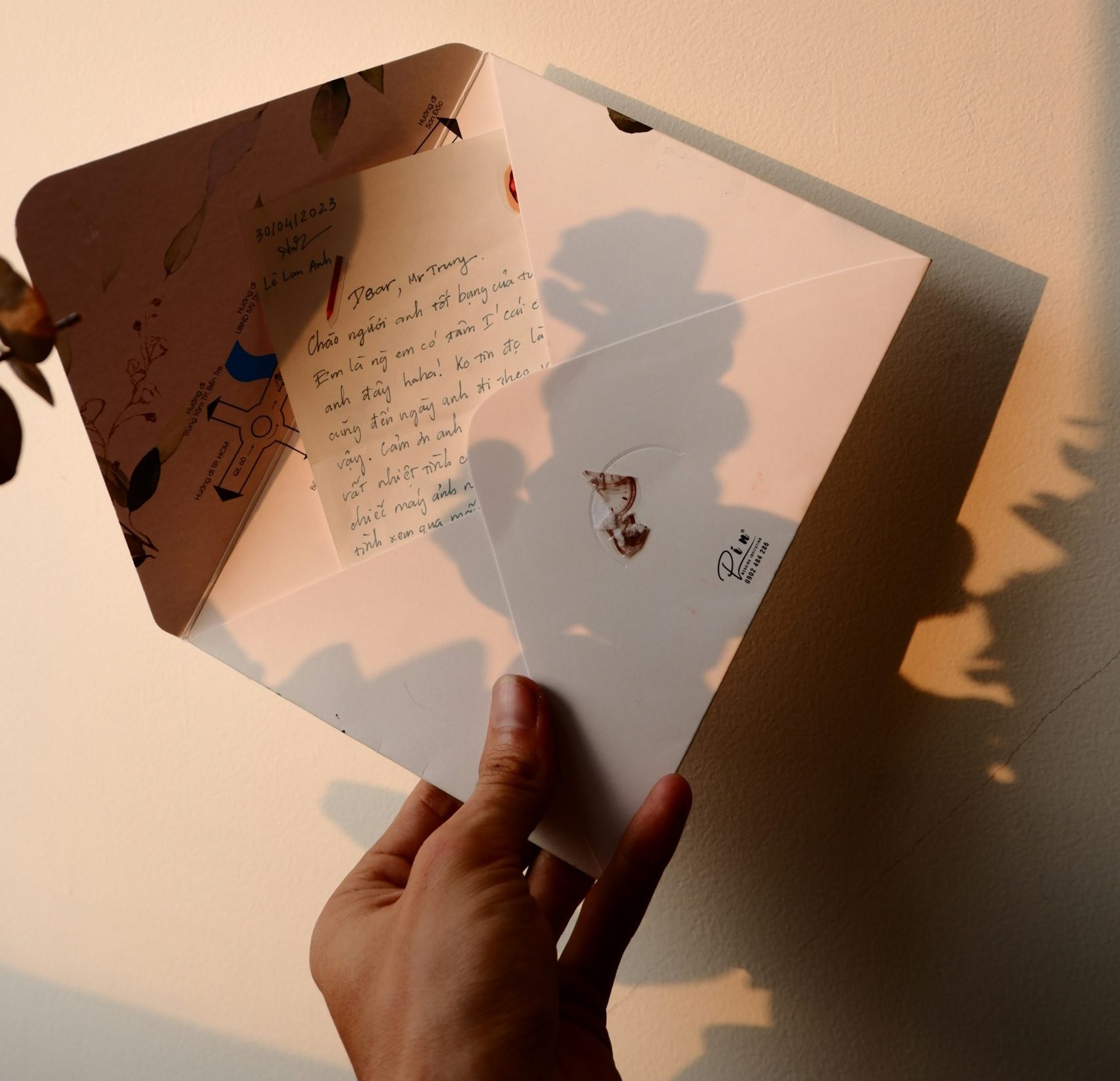

It was only the picture beside the window after all.

Read Church Chronicles 5 Sabbath

3 thoughts on “Through your Eyes | Church Chronicles 6”